Dear James…

Even a simple act like shipping an object can trigger a series of symbolic and ideological transformations with tangible effects. Planning a special dinner in Ushuaia, Argentina, Mahony Collective intended to serve a potato dish with sauerkraut. However, sending the sauerkraut from home turned into a bureaucratic nightmare. Despite numerous attempts to retrieve it, the group faced obstacles due to import regulations. Eventually, they abandoned the barrel at the shipping depot.

The failed shipment led to the sauerkraut's transformation from a foodstuff to an artwork, then to freight, and back to an artwork, only to end up as an ambiguous object. The groups experience highlights the arbitrary nature of bureaucratic systems and the fluidity of object identities. Despite their efforts, they couldn't rescue the sauerkraut, leaving it in bureaucratic limbo.

The incident also reflects the Collectives broader topics of movement, exchange, and the hidden layers of information. Their use of the potato as a symbol underscores these themes, emphasizing the circulation of objects and the deeper meanings concealed beneath the surface. Ultimately, the sauerkraut saga serves as a microcosm of Mahony's exploration of the complexities of globalization and cultural exchange.

Text excerpts by Matthew Post

Dear Senior Curator of the End of the World Biennial,

I am writing this letter to explain why I was unable to bring the sauerkraut for the End of the World dinner.

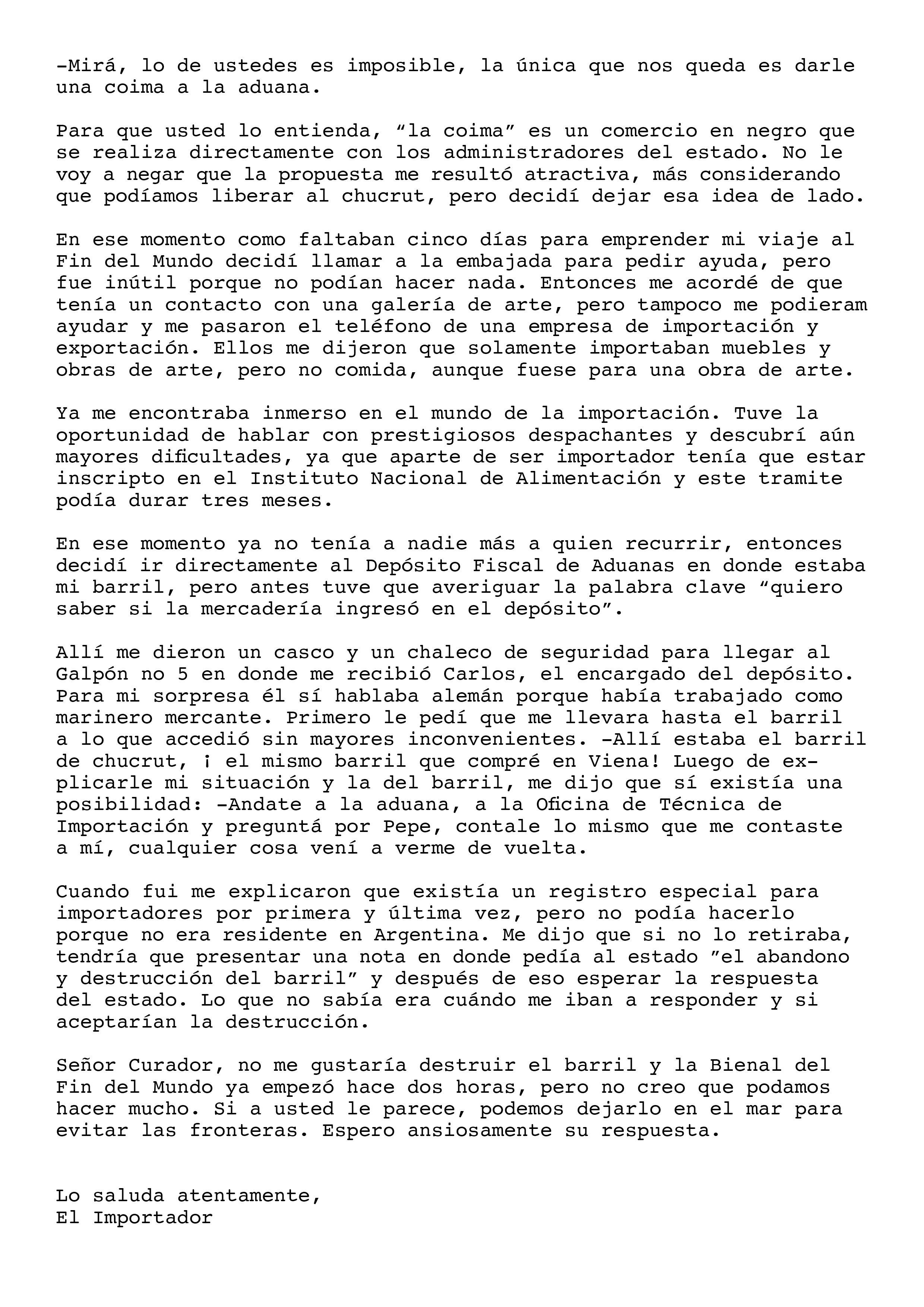

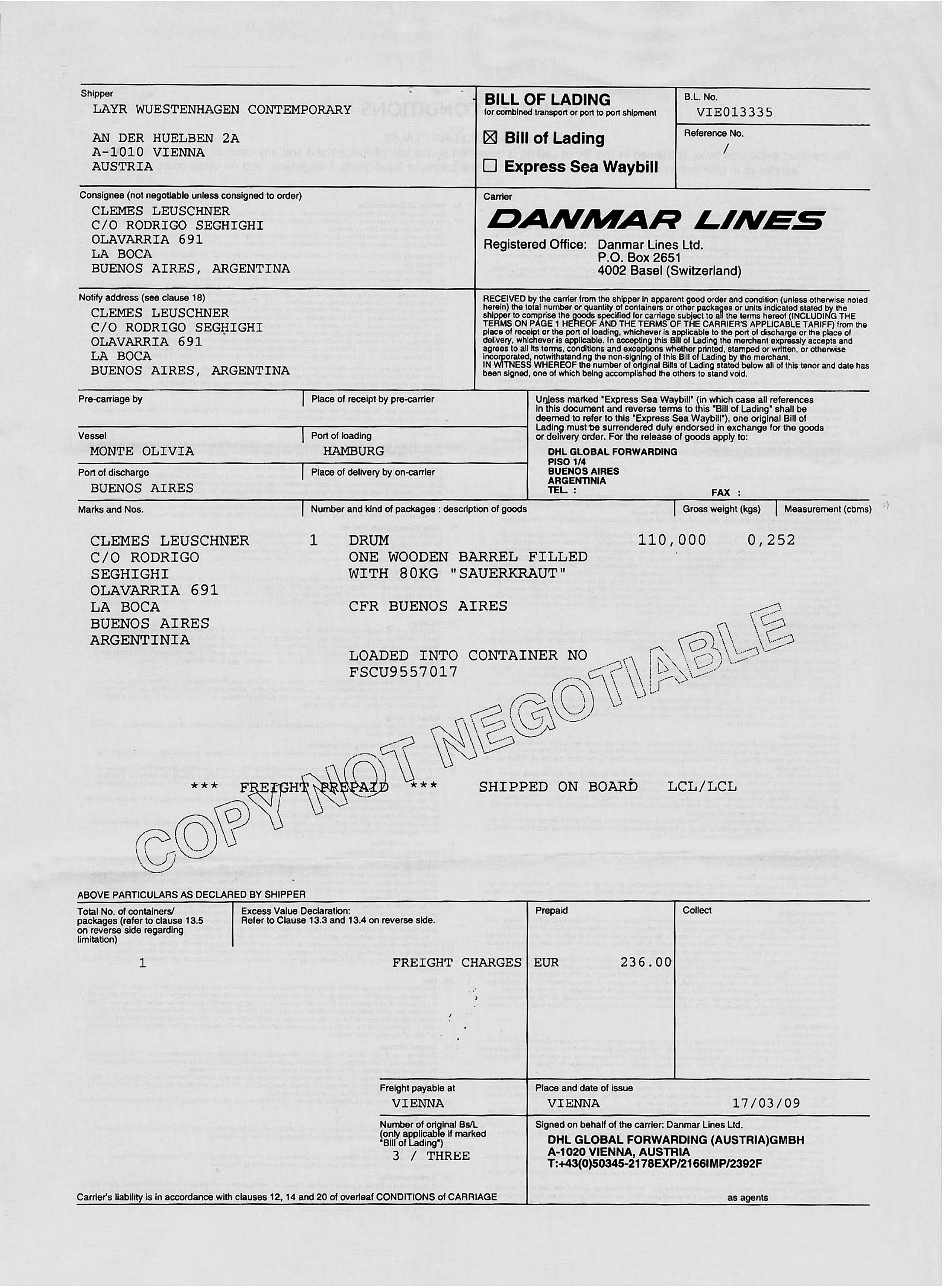

The barrel of sauerkraut departed in a truck from the 11th district of Vienna to Bremen, where it transferred to another truck headed to Hamburg, from where it finally set sail on the ship Monte Olivia. The ship made several stops: France, England, Senegal, and Brazil, before arriving at the port of Buenos Aires on April 5th.

Once in Buenos Aires, I contacted the Commerce office that transported the barrel to inquire about its arrival. Here arose the first problem: "The lady at the Commerce office asked me who was going to import the barrel, and I immediately explained that it was I who was importing it. This was the beginning of the odyssey.

The Commerce offices in Buenos Aires are all located near a mast that everyone calls the obelisk. When I went personally to the Commerce office, I discovered the importance of being an importer, a matter that no one had warned me about before leaving Vienna.

Faced with this situation, I decided to "initiate" myself as an importer. This seemed to be the only legal possibility to bring it into the country. I had to go to Customs to get information, and there they explained that I had to register in a National Importers Registry, but first I had to register with the Public Revenue Administration, a place I could visit and get to know - Senior Curator, you can imagine that for me communication in a southern country was very difficult since I couldn't speak Spanish correctly to worsen my situation, at the information desk I was attended by a person with speech disabilities, so I directly took a number and prepared to wait for four hours.

When they finally attended me, they explained that I first had to go to the Immigration Office, which is very close to the old immigrants' hotel from the late 19th century. At the Immigration Office, the scene made me imagine those European immigrants from centuries past who came to Argentina. When I finally managed to enter and be attended to, they explained that I had to process residency in the country and showed me a list of occupations and requirements. I was in the category of artists and athletes, but for that, I had to go back to Vienna for my police records, birth certificate, etc. I had never thought of settling in Argentina, much less to be able to bring in a barrel of sauerkraut!

Another discovery I made was the existence of "customs brokers." They are responsible for customs procedures, so I decided to meet one. When I finally found a customs broker, he explained the difficulties of bringing the sauerkraut into the country because I was not an "importer," but what struck me the most was what he said next: "Look, what you're trying to do is impossible, our only option is to bribe customs." For you to understand, "bribes" are transactions conducted in the black market directly with state administrators. I won't deny that the proposal seemed attractive to me, especially considering that we could release the sauerkraut, but I decided to set aside that idea.

With only five days left before my trip to the End of the World, I decided to call the embassy for help, but it was useless because they couldn't do anything. Then I remembered that I had a contact with an art gallery, but they couldn't help me either and they gave me the phone number of an import-export company. There they told me that they only imported furniture and works of art, but not food, even for a work of art.

I was already immersed in the world of importation. I had the opportunity to speak with prestigious customs brokers and discovered even greater difficulties, since apart from being an importer, I had to be registered with the National Food Institute and this process could take three months.

At that moment, I had no one else to turn to, so I decided to go directly to the Customs Warehouse where my barrel was, but first I had to find out the keyword "I want to know if the merchandise entered the warehouse." There they gave me a helmet and a safety vest to get to Warehouse No. 5 where Carlos, the warehouse manager, received me. To my surprise, he spoke German because he had worked as a merchant sailor. First, I asked him to take me to the barrel, to which he agreed without major inconvenience.

-There was the barrel of sauerkraut, the same barrel I bought in Vienna!

After explaining my situation and that of the barrel, he told me that there was a possibility: "Go to customs, to the Import Technical Office and ask for Pepe, tell him the same thing you told me, if anything happens, come back to see me." When I went, they explained to me that there was a special registry for first and last-time importers, but I couldn't do it because I wasn't a resident in Argentina, they told me that if I didn't withdraw it, I would have to submit a note to the state requesting "the abandonment and destruction of the barrel" and after that, wait for the state's response. What I didn't know was when they would respond to me and if they would accept the destruction.

Senior Curator, I wouldn't like to destroy the barrel and the End of the World Biennial started two hours ago, but I don't think we can do much. If you agree, we can leave it at sea to avoid the borders. I eagerly await your response.

Yours sincerely, The Importer

The text was part of the performance Kartoffelessen (potato dinner)

Mahony Collective, in collaboration with Ezequiel Monteros. Biennial at the End of the World, Ushuaia, Tierra del Fuego, Argentina, 2009.

Spanish original text by Ezequiel Monteros.